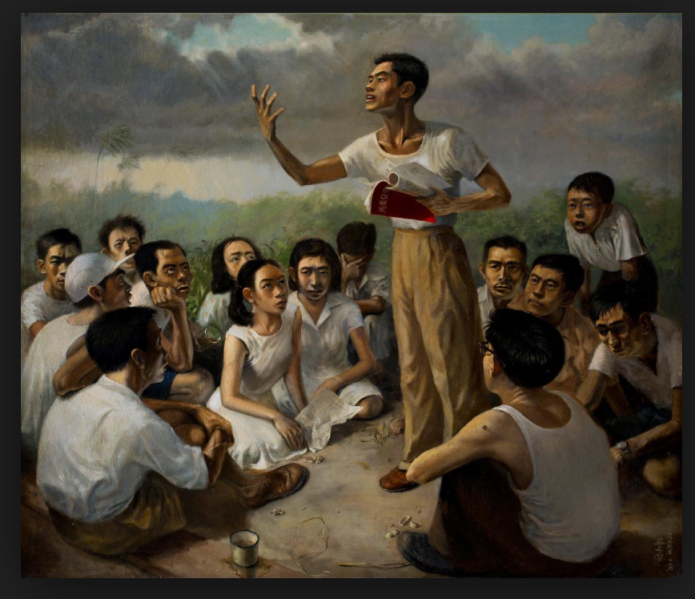

Han Suyin stands in the middle of the cavernous gallery displaying only one painting. The man in a white short-sleeved singlet stands in the middle of the painting. He holds a red book in his left hand, his right arm is extended, forearm raised in an L-shape, with his hand and fingers facing him in an awkward twist. This is a hand that commands attention. His khaki trousers are creased but his young face shines with determination as he recites a poem from the red book. He looks into the distance and not at his audience. The distance is where he sees himself in the future, the future of Malaya.

Suddenly, a gust causes the debris at Han Suyin’s feet to spin like a whirligig: insect carcasses, dead leaves, brown and shrivelled, twigs of all lengths circle around her, rising over her head and disappearing into the massive jungle above. Monkeys shriek, crickets chirp and snakes swish amongst the tall lalang grass, the cacophony deafens her. Mosquitoes prick her sweaty calves as she swats away the rest threatening to suck blood from her arms. The foliage is so thick that Han Suyin can’t see the wall of black clouds forming above. But she can smell the imminent rain, its humid vapours mingle with the stench of mud, mulch and madness. The wind dies down and the air becomes oppressively still—a sign that the skies will soon crack open. She’s inside a white cube yet she feels the tension. There’s danger everywhere but the comrades have told her the jungle is the safest place right now since the jipun kia, the Japanese, have left bringing the British red-haired devils back. Her distant future seems as bleak as the tarpaulin tents she’s forced to sleep under. The white cube disappears.

Suet Ling is fanning a fire where a blackened pot hangs above. She is squatting, legs splayed by her swollen tummy, her bottom almost touching the muddy ground. Mei Ching squats next to her, plucking feathers from a recently slaughtered jungle fowl whose death was caused by decapitation. Its severed head lies nearby, tossed aside as Mei Ching held the flapping bird down so that its headless body will not escape. She doesn’t wait for it to stop flapping before she plucks away at the bird. It’s a rare treat to be having fresh meat for dinner. Rice is rationed, brought in pocketfuls or hidden in the rubber tappers’ shoes which is then passed on to the People in the Jungle. Communist Terrorists as they’re known. It’s sweet potato leaves for fibre again.

Suet Ling lets out a groan, hands holding her stomach, she attempts to stand up. Her legs wobble and a gush of liquid pooled around her feet.

“I think baby come,” she says to Mei Ching who throws the naked chicken into the pot.

“Quick, quick, we get doctor,” replies Mei Ching as she runs off to untie Han Suyin.

The men are all on guard duty and will not be back until night breaks; two have been sent to punish a traitor who will be beheaded in a ceremonial execution. Han Suyin, Suet Ling and Mei Ching are the only people left in the camp. The latter two are watching over Han Suyin, the doctor whom their comrades had kidnapped from the clinic in town along with medical supplies.

Han Suyin tremors while she looks into the frame catching the eye of the girl in white sitting by the speaker’s feet. Can that girl really be Suet Ling who died while giving birth to her breeched son? The comrades had blamed the baby’s death on the doctor, on her, and she was punished severely. What about the girl holding a piece of paper? Is she Mei Ching? She must be. Han Suyin thinks she recognises those fervent, determined eyes looking up at the speaker who she thinks is Comrade Lee Loke Wan. He would have executed her if not for Mei Ching’s interference.

“What for kill doctor? She can help us.”

“Don’t interfere, woman!” a rifle cocks. “She lucky I not hacking her with a parang. I waste one bullet to kill her because she is a woman. Don’t say I not kind! My woman and son are both dead. I want revenge.”

“Suet Ling unlucky, lah. Who can say why baby feet come out first? Not the doctor’s fault, Ah Loke. This kind of thing is heaven send one. Suet Ling never pray to Guanyin, that’s why. Killing doctor will make Guanyin Mother more angry, then our camp cursed. Cannot like this, Ah Loke.”

Han Suyin listens, hands tied behind her back, blindfold over her eyes. She is kneeling as another male comrade holds her still. Mei Ching’s voice is soft, reasoning, determined to win Comrade Lee over to her side. Han Suyin realises that her life is in this woman’s hands.

In this cavernous space, she wonders what has happened to these people in the jungle. She shivers as she remembers those dark days.

When the Malay police officers found her, Han Suyin weighed only 32 kilograms. After Suet Ling’s baby died, her meals were reduced down to one a day. Her menses had stopped and she could no longer tell the time from day to day. The people in the jungle had lost faith in her as a doctor. But it was Mei Ching, the nurse, who managed to keep her alive. Mei Ching had only worked a few months at the clinic where Han Suyin was abducted. It was Mei Ching’s idea to have a doctor in the camp. But without the right medical supplies, Han Suyin couldn’t do much. Suet Ling bled to death as her son remained wedged between her legs.

The camp was dismantled as the commanding police inspector, Leon Comber, rounded up the men and women of the jungle and loaded them into a truck. They will be dealt with by the Crown courts later; some will hang for murder. Special Constable Comber held Han Suyin, his wife, tight. It had taken the British administration six months to find her. She allowed her skeletal frame to lean into Comber’s tight, secure chest, relieved that her ordeal is now over.

About the Author:

Eva Wong Nava writes Flash Fiction to find catharsis. She is published in various places, including Jellyfish Review, Peacock Journal and Ariel Chart. She founded CarpeArte Journal as a blog to publish her own work and to give a platform for others to do the same. Since then, the Journal has grown to include writers and poets from around the world.

Eva is also a children’s book author. Her book, Open: A Boy’s Wayang Adventure was written to help readers be more compassionate to people on the autism spectrum.

Eva’s Comments:

As the managing editor of this growing journal, I’ve not had much time to write recently. Submissions are flowing in, thanks to many talented writers in the Flash Fiction community. There have been poems ebbing in too, thanks to the many prolific poets out there.

This story had to be placed on the back burner for a few months as I sat on various writing projects and researched Malayan history for a book I’m writing. I have been toying with the idea of introducing a character who is a real person but giving said character a fictional space within the form of flash.

Han Suyin was the pen name of Elizabeth Comber, a China-born Eurasian writer who wrote the 1952 book, A Many-Splendored Thing which was made into a movie entitled Love is a Many-Splendored Thing in 1955; many old enough will remember the song with the same title. Her second novel, published in 1956, also with a poetic title, And The Rain My Drink, was set in British Malaya during the Malayan Emergency. This novel and her political convictions cost her her divorce from her second husband, Leon Comber, a British officer in the Malayan Special Branch.

About the Artist:

Chua Mia Tee remains one of my favourite Nanyang artists who paints in a style known as Social Realism. Although Chua is not included in the list of Nanyang artists who gave their name to an eclectic art style known as the Nanyang style, Chua’s works are still important documents of Singapore’s history and commentaries on the social fabric of the country, its people and its politics. I don’t think Chua meant to be overtly political as this was not his focus; he was more interested in documenting how the people lived and bonded during a turbulent period in Singapore’s history. Identity was an important concept to him and to most Chinese emigres of his time: are we Chinese or Malayans? Chua explores this notion in another painting, ‘National Language Class’ which he painted in 1959, the year Singapore gained self-governance from the British.

His subjects were mostly the people he knew intimately, like his wife and close friends. He believed that art’s function was to educate by sharing ideals and visions that will lead to changes for the betterment of society.

‘Epic Poem of Malaya’ (1955) depicts a scene where a group of young Chinese students from Malaya are seated around a young man reading from a book. These youths were keen to develop a sense of Malayan identity during this period of Singapore’s and Malaysia’s history, a period during which guerrilla wars were being fought in the Malayan jungles against the British administration. The guerrilla wars were organised by mostly Chinese speaking and educated emigres who saw Communism as the best form of governance and ousting the British as a goal towards gaining independence. A Malayan identity was important for the unification of a predominantly Chinese people, who were neither natives nor Malayan-born, and who had no wish to return to China although they identified Chinese.

What I love about this painting are the minute details, like the fly sitting on the bare shoulder of the man on the right, for example. Check out the facial expressions of his characters/subjects; I love the gobsmacked expression of the boy at the back. Can you see a man whose drink is almost spilling because he’s so engrossed in the recital? Note the peanut shells scattered on the ground.

Its title reads like an ode because the painting is indeed an ode to Malaya. ‘Epic Poem of Malaya’ evokes a sense of nostalgia in its viewers. For many who remember this not so distant Malayan past, this painting brings back a lost sense of idealism. British Malaya no longer exists. Made up of British protectorates of the Malay States and the Straits Settlement under the British, this geographical entity has morphed into Malaysia and Singapore, with Singapore independent from Malaysia since 1965. Have Malaysians and Singaporeans lost their ideals?

Chua Mia Tee was born in 1931 in China and emigrated to Singapore (British Malaya) in 1937 with his family who was fleeing the Sino-Japanese war, not realising that the Japanese forces would infiltrate Southeast Asia in a few years’ time. Being one of the many people from the pioneering generation of Singapore, Chua Mia Tee experienced the Japanese Occupation of Singapore, the return of the British after the war, the Communist war against the Empire, and the nation’s fight for independence during the 1950s, culminating in Singapore’s independence in 1965. He documented this turbulent historical period in oil paintings that can be found at the National Gallery Singapore today.

Chua, Mia Tee (1955), Epic Poem of Malaya, Oil on canvas, 112 x 153 cm, Collection of National Gallery.